Blog

Celebrate World Book Day with WriteReader

World Book Day celebrates authors, illustrators, books, and, most importantly, reading. Celebrate World Book Day with WriteReader by honoring books and encouraging children to explore and learn the written language.

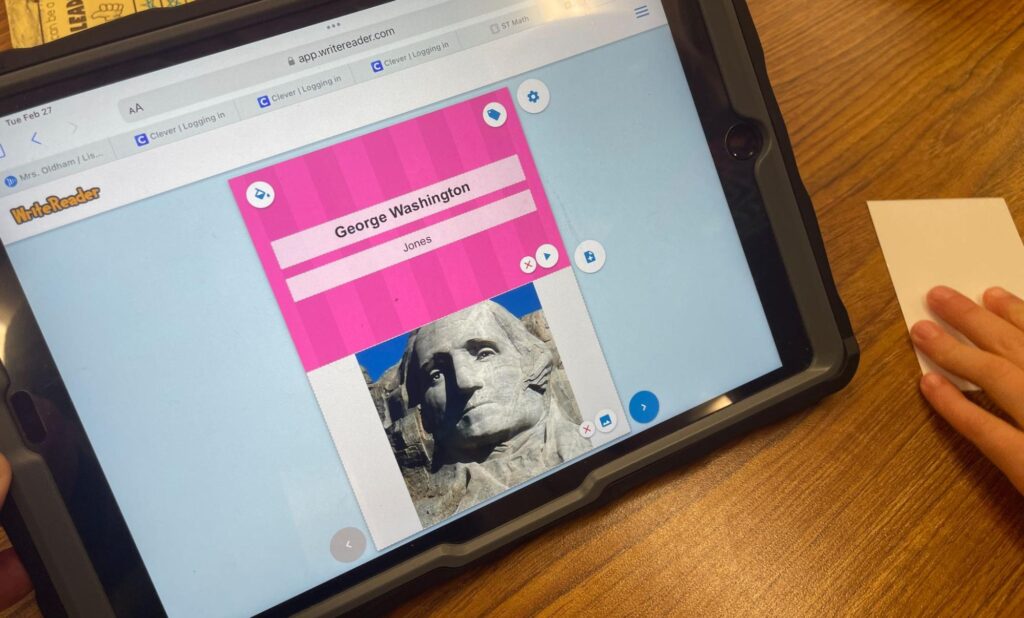

Make Writing Fun & Engaging with WriteReader’s Multi-Sensory Learning Approach

My class has been using the WriteReader tool for the past three years. At the start, I used it to make writing fun and motivate my students who needed a

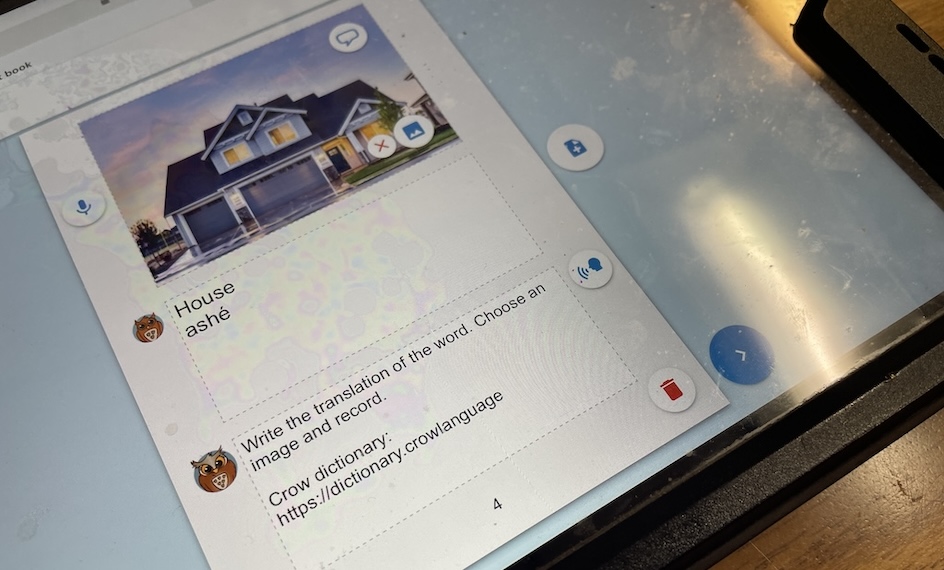

Preserve Indigenous Language with Dictionaries in WriteReader

After reading the powerful story Stolen Words, by Melanie Florence, to 2nd graders, we wanted to create an opportunity for students to discover, hear, and interact with indigenous languages. WriteReader

Celebrate Ramadan, Faith, and Writing with WriteReader

The holy month of Ramadan is perfect for encouraging young students to reflect upon diverse beliefs and traditions, and celebrate Ramadan, their culture, faith, and writing. With WriteReader, students have

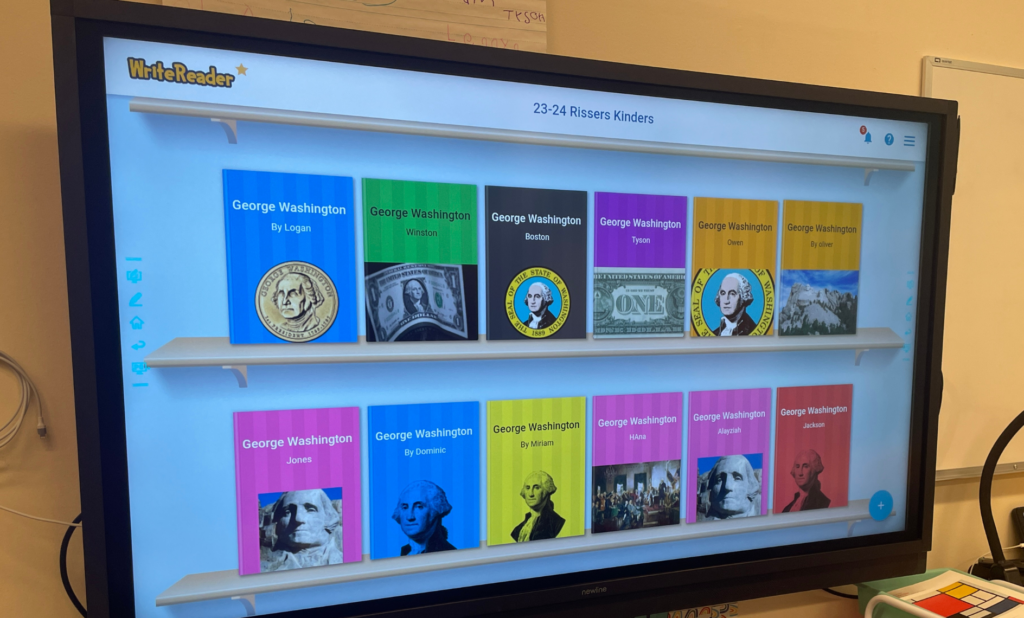

WriteReader: A Scalable and Cost-Effective Solution for Literacy Development

Years of research have made one thing abundantly clear: children learn more when they are passionate about the subject matter. With WriteReader, they achieve this by creating and sharing their

Get Your WriteReader Premium Subscription Funded

In the world of education, resources are key. But sometimes, those resources need a little help from the community. That’s where DonorsChoose comes in. This amazing platform allows educators to